Chicago, recently: In defiance of his grim diagnosis, a beloved wine shop owner throws an epic party, opening his rarest bottles for his favorite customers. But none of them are fully prepared for the complexity, body, and depth of what is about to pour forth.

Cast (in speaking order):

BOBBY CANNAVALE as The Narrator

TIA DeSHAZOR as Heather

JOE MANTEGNA as Barry

JEFF STILL as Mitch

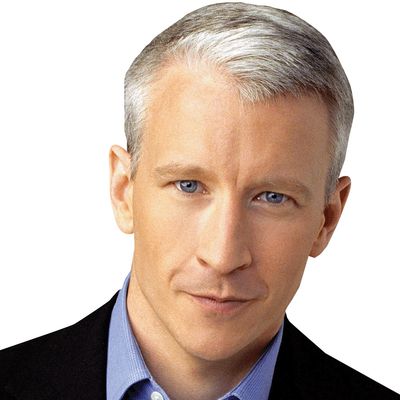

ANDERSON COOPER as Raymond

ANDY COHEN as Ned

GIA MANTEGNA as Tara

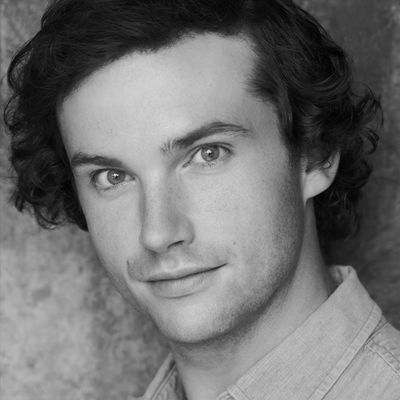

TYLER HANSEN as Matthew

PATTI LuPONE as Myra

with SAM TSOUTSOUVAS, the voice of RPR