Barry Joseph: Welcome dear listeners, to a special episode of Matching Minds. In Sunday in the Park with George, the character Dot sings to George: "give us more to see." Well, this is the "Give us More to Hear" episode. More Richard Schoch. More Last of Sheila. More of my appearances in other podcasts. More. More. This is the episode I originally conceived of as a bonus episode with pieces cut from earlier ones and well, it still is, but as I began to edit it, a shape began to emerge. Let's use my Schoch interview to frame it all. We'll begin and end with Richard and sprinkle our conversation throughout this hour. Together, we'll revisit my conversation with Richard and for the first time explore the places where our two books on Sondheim talked about the same thing, but in different ways.

I also awkwardly correct something in his book, which he graciously accepted, and we'll end with his offering advice to me as an author just weeks from my book coming out. And in between you'll hear... well, more. You'll hear James McCusker and I dig deeper into the jigsaw puzzle promotional swag developed for the 1973 Sondheim murder mystery film, The Last of Sheila. And for the first time, you will get to hear member-only bonus content from my appearance on The Room Escape Artist podcast, where we dig into my experience playing the first ever alternative reality game, The Beast, and how experiences like that were transformative for both me and my hosts.

So join me as I attempt to give you something more.

Barry Joseph: So let's bring back Richard Schoch. Richard is the author of How Sondheim Can Change Your Life, which just came out this month in paperback. In the first podcast, episode six, we dove into the emotional and intellectual processes behind writing books about Stephen Sondheim. Now, please listen in as we look at where we took elements from Sondheim to make a point, but different points. We do this to emphasize our different lenses: Richard's self-reflective, mine, ludological or playful. And we'll start with Anyone Can Whistle.

What I would love to do now, is keep going through our books. But I'm going to highlight the places where we both talked about the same thing, but in very different ways.

Richard Schock: Okay.

Barry Joseph: Because your lens is about how someone can learn something from it, and I'm talking about how it tells us about his puzzler's mind. So it it was very fun for me to read your book and be, "oh, look what Richard did with this, and I did that!" And we can start right in the introduction, you talk about the song, "Simple". Which is at the end of Anyone Can whistle, at the end of the first act. You do something different than I. Can you say a little bit about how you used it and I'll talk about how I used it? And again, what we're doing here is we're focusing on our lenses. To have a lens means we are saying, we are holding out to you as a reader, a tool set for viewing something. We want you to apply it to Stephen Sondheim, but you can apply it to all sorts of things. And we're going to keep modeling again and again how one uses this tool to view and analyze something in a new way.

What we're going to look at now is a few examples of how we both looked at the same thing, but with our lens we saw something different.

Richard Schock: Right, so, "Simple", the song that ends the first act of Anyone Can Whistle, Hapgood, who seems to be the psychiatrist, but is actually one of the patients or inmates of the quote unquote "Cookie Jar", the lunatic asylum. He stares at the audience and says, the lights have dimmed. It's just a glow on his face- and he says, "you are all mad", says that to the audience. And there's crazy circus music. And then the lights come up again, and the cast is sitting in a row of theater seats, fanning themselves with their programs, and they start to laugh and point at the audience. Now, the dramatic point here being made is that we all have roles that we play in our lives, and that's true. Either roles that we cast ourselves in or, just as often, roles that other people's cast us in, sometimes against our own will. But, we are often acting for others and others are acting toward us to create a certain impression. So that seems to me the message that Sondheim was trying to get across and it's true and it's valid. And the point I'm making is what Hammerstein taught Sondheim was you have to put the audience first. In this production, Sondheim did not put the audience first because he mocked the audience. He ridiculed the audience by having the cast laugh at them. And Angela Lansbury, who played Cora Hoover Hooper in the original production, she's on record as saying, "one of the reasons we closed so soon, is because this show made an ass of the audience".

That's her word. And that's probably not a great thing to do if you want to keep the audience. So, one of the things I try to say at the beginning of the book, which is Sondheim had to have this complete failure after the success of Gypsy and West Side Story to finally learn the lesson that the audience comes first.

And that every musical theater song, every musical theater work is ultimately about the audience. And don't laugh at them.

Barry Joseph: When I read that analysis in the book, I loved it. And yet, that's not how I used it in my introduction. I start a beat before you.

Richard Schock: Right.

Barry Joseph: As you tell it now, you're talking about when Hapgood says, "you're all mad". But before he says they're all mad, he splits people in the town into two groups, "group one" and "group A". He has just released the inmates from the mental hospital. They've mixed themselves with the townspeople and he's going to separate them. Someone's going to go into "group one" or someone's going to go into "group A", but he's refusing to say which ones are the inmates and which ones are the townspeople. My book started as an analysis of Sondheim's puzzles and games. It's told organized by the games and puzzles. But it also has this biographical component that I was talking about earlier. So it reads like a solid piece of literary non-fiction. But I also wanted to include resources. How do you play Sondheim's games? Where can you see puzzles that are like his? So I have two sections. But I didn't want it to be a first section and a second section. So I called the first one "Group 1". And I call the second one "Group A".

Richard Schock: Brilliant.

Barry Joseph: I then explain what you and I know about, and I say, like Hapgood, I hope to conflate separate groups: Sondheim fans, game players, puzzle solvers, even book lovers, to celebrate how deep obsessions, pursued with good intent in a supportive community, can elevate us all.

Richard Schock: I love that. You've used the libretto to good advantage.

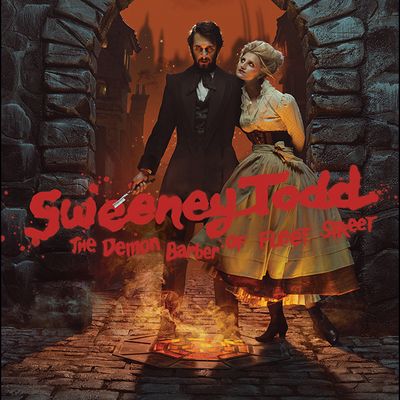

Barry Joseph: Speaking of librettos, let's jump to Sweeney Todd and look at "A little priest."

Richard Schock: Okay.

Barry Joseph: That was a discussion about Anyone Can Whistle. Next, Richard and I will discuss Sweeney Todd and then Sunday in the Park with George. But first, let's return to episode 11. The Last of Sheila. You might recall, James McCusker and I discussed the promotional material produced for the film, such as the Al Hirschfield print. Well, in that episode we left one thing out: jigsaw puzzles.

Barry Joseph: Something we haven't talked about yet are the jigsaw puzzles that were mailed to people. I learned about those jigsaw puzzles from you, James, what do you know about them?

James McCusker: So there was a number of jigsaw puzzles each one was a character from the film.

Barry Joseph: Eight boxes. Eight puzzles. One for each character, including Sheila. When I arrived at the pre auction exhibit at Doyle's in New York City, one of the things I was most excited by was not only seeing the boxes that I'd only known about through photos you'd shared with me online, but getting to actually open them up, drop those puzzle pieces on the table, and for the first time find out what was inside. They're essentially a photo of the actor or actress and some really badly written copy on the bottom. This is the one of Dyan Cannon, which I show in the book and they're all so goofy. Can you read this one for us?

James McCusker: Oh, sure. "Christine is an agent. Christine is powerful. What is Christine's secret?"

Barry Joseph: And then in bold.

James McCusker: "Dyan Cannon is Christine. That's fantastic."

Barry Joseph: And this one is, uh, this is Clinton with a cigarette staring you in the face. Can you read this one?

James McCusker: "Clinton is a movie producer. Clinton was Sheila's husband. What is Clinton's secret? James Coburn is Clinton." Bold print.

Barry Joseph: Now this one, I think is the, it is the worst one. It is 15 pieces and it shows Joan Hackett like screaming with a blurry object. Now if you know the movie, you know what she's doing. She's being really aggressive towards somebody. But in the picture, if it was me I'd be embarrassed. It's just an awful photograph.

James McCusker: " Lee is Tom's wife. Lee is anxious. What is Lee's secret? Joan Hackett is Lee". I have never seen that puzzle. I have not seen this one. That is a, it's a spoiler.

Barry Joseph: It's a spoiler.

James McCusker: I know they were sent out for promotion, but it's ridiculous that we don't have a picture of her on a sundeck somewhere.

Barry Joseph: Yeah. James, I don't know what they were thinking when they put this one together. And what does that mean? "Lee is anxious". That's the best they could come up with for this character?

James McCusker: For not only for that character, for that photo. I mean that's really what it's about. She looks awful anxious, and uh, I'm under the assumption people have seen the movie, so we can say she's holding a giant candle stick that she just crashed through a confessional.

Barry Joseph: There's probably blood on the end of it.

James McCusker: Obviously, obviously.

Barry Joseph: Okay. This one I think I put in the book as well. No, I think I wrote about it in the book. Can you just describe this image?

James McCusker: Raquel Welch looking like a femme fatal. " Alice is a starlet. Alice is ambitious. What is Alice's secret? Raquel Welch is Alice."

Barry Joseph: That look on her face. It's like they said: look to the left and imagine you just saw an alien burst out of the ground. She just looks dumbfounded.

James McCusker: I have no idea. You know, Bob Pan, the great still photographer was the photographer for publicity on Last of Sheila. I have no idea if these color shots are his or not, but... strikingly artificial.

Barry Joseph: I, I think poor, poor Raquel, when I see this one.

James McCusker: Poor Raquel. Come hither look.

Barry Joseph: This is my favorite one 'cause it's just so ridiculous. Are you ready?

James McCusker: Oh, this is horrible, right?

Barry Joseph: Can you describe it please?

James McCusker: Yeah. Well, it's Sheila, uh, a bit of a mess after the hit and run accident covered in blood. Dead. And it says "Sheila is a gossip columnist. Sheila is dead."

Barry Joseph: That's it. That's it.

James McCusker: The Last of Sheila!

Barry Joseph: It's the last of Sheila. It's all she wrote. They don't even say who Sheila is. the other ones get the names of the actress and actresses. This one just says Sheila's dead.

James McCusker: She's a gossip columnist

Fantastic.

Barry Joseph: Fantastic indeed. It's always a good time when James is around. Let's return now to my conversation with Richard Schock, as we discussed the different ways we used the same bits from Sweeney Todd and Sunday in the Park with George.

Let's jump to Sweeney Todd and look at "A little Priest."

Richard Schock: Okay."

A Little Priest" is the comic duet that ends the first act of Sweeney Todd, but it comes after a very serious solo sung by Sweeney called " Epiphany", in which he vows vengeance upon the entire world. "Not one man. No, not 10 men nor 100 can assuage me". So it's this incredibly dark moment where Sweeney is going to become a killing machine, and there's no applause. Sondheim didn't want it. And then it segues into " A Little Priest."

Let me read for you a couple paragraphs from the book about "A Little Priest". Sweeney joins this morbid scheme- that's Mrs. Lovett's scheme, to have Sweeney kill his customers and then turn them into meat pies. Sweeney joins this morbid scheme and the two of them spin out their fantasy of capitalist cannibalism in "A Little Priest". The grisly list song that brings the first act of Sweeney Todd to its rousing finish. They conjure an endless line of victims, priest, grocer, tailor, clerk, fop, and one day soon, judge, to assuage Sweeney's bloodlust and to earn Mrs. Lovett enough coinage to line the purse she has just filched from a corpse.

This is where Sondheim wanted the applause and he got a storm of it. Yet, "A Little Priest" is nothing other than "Epiphany" wearing the mask of comedy. Sweeney's murderous rampage, far from receding, gains new strength in its intricate plotting. Exactly what, then, are we applauding? Not so much Sweeney's carnage, we've heard about that already, as our own ability to tolerate it.

Barry Joseph: That gives me chills just hearing you read that.

Richard Schock: Well, it's a chilling moment in Sweeney Todd, but in a very Sondheim way, you're laughing all the way through this moment and then you suddenly realize how horrible it is. And it's more chilling because you think it's comic. And that's Sondheim's genius. He's constantly- wrong-footing is maybe not the best phrase- but he's constantly mixing and blurring emotional registers so that what you think is comedy is actually tragedy. And what you think is tragedy turns comedy.

Barry Joseph: And I think that analysis is very valid. And I experienced it somewhat that way as well. And yet from the lens of my book, you'll hear something completely different. I'm not going to read it to you. I'm just going to describe to you how I talk about this song, "A Little Priest", in the book. And to do so means I have to go back a bit to the 1970s to talk about some early game theory. Bernie De Koven, who called himself the "Shaman of Play", led something called the New Games Foundation in the 1970s. I don't know what you were doing with play in the 70s, Richard, but for me that was gym class in elementary school, and that meant parachute games and giant earth balls. These were games that were created in the 70s, kind of this kind of hippie evolution into these big public gatherings that redefined what play looked like, and they were called New Games. Many people in the youth development space know these books and use them for decades. Bernie didn't just help design these games, he also wrote about them and he wrote some play theory. And one of his most important contributions is the idea of a "well played" game. " Well-played", something you might say to an opponent, whether they beat you in a competition or they lost to you, you're appreciating that they played their best and they brought out the best in you. It's the idea that when we play together, the most important thing is not winning, but that we bring out the best of each other. And that by playing hard and matching what we're given by our opponent, we elevate the game for everyone, including those watching. Sweeney and Lovett are in a verbal competition. They're each trying to outdo the other. that want to extend the game as long as possible to relish in how it's unfolding. So when it ends, and we're clapping, we're applauding them for a well played game. For the characters with each other and for Sondheim playing with us..

Richard Schock: I think that's absolutely right. And they take incredible delight in playing that game, which has very specific rules. You have to name an occupation and then you have to do a pun with how that can translate into a meat pie. And there's this wonderful moment where Mrs. Lovett wins her point when, you know, they do, " butler, subtler", " potter, hotter", you know, as "I can top you with the rhyme". And then she just goes " locksmith". And there's no rhyme, so she wins the point.

Barry Joseph: And we all laugh.

Richard Schock: We do, we do. We're enjoying it. It is a tour de force game for sure. And again, this is a tribute to Sondheim's genius, which what you've said about the song and what I've said about the song, I think are both valid approaches and we don't have to decide between them. We can have all of these approaches because the material is so rich.

Barry Joseph: Thank you, Sondheim. There's a third example, and there's many more, but there's a third one I want us to look at together. And this one is on page 135, where we both quote from James Lapine's oral history of Sunday in the Park with George.

Richard Schock: How funny.

Barry Joseph: But we do it in very different ways because of course we have very different things to say about it. So in the book, which is pretty much the opening of the book, James Lapine is talking about where Sondheim is at when they first met. Merrily had just flopped on Broadway in 1981 and Sondheim is really down. And so what's the quote you chose to use? And can you say a bit about why? And then I'll talk about what I did with the quote and why.

Richard Schock: "I don't want to be in this profession. It's just too hostile and mean spirited." And it doesn't get any starker than that. I think Sondheim hit professionally, emotionally, rock bottom after the failure of Merrily, and it really rattled him and thank God he did not leave the profession. But, can you imagine having to go through that? And you think even Stephen Sondheim had a crisis so severe that he thought the better course was to stop writing and stop composing. Thank God he didn't follow through.

Barry Joseph: And Richard, you rightfully focused on the fact that this is a moment of him struggling with the failure and considering leaving theater. But I also rightly focus on where he talked about going instead, which you do not include because that's not relevant for you, but it is for me. So, I'm not going to read you how I put it in the book, but I'll read you the full quote that I pull from. And you'll understand why in a moment. So listen for the overlap and listeners will hear what's different. "I thought, I don't want to be in this profession. It's just too hostile and mean spirited. What else can I do? I thought, I'd love to invent games. Video games. That was what I really wanted to do".

My book is about what he was fantasizing he would do instead. You write about what he then ended up doing and learned from as a result. That quote, when I read it, when I was reading those first few books that I mentioned after he passed away is what led to my entire book. Because I heard that, "he wants to make video games? What?" And that's never mentioned again in James Lapine's book, Putting It Together. And I thought, "I have to get to the bottom of this". And that's where my book came from.

Richard Schock: Fantastic. You know, I had forgotten that that was the second half of the quotation. And in a way, it's, you know, hilarious 'cause you think, you know, this is the early 1980s. What were video games like? It was, I don't know, Pac-Man in the early eighties. Very, very rudimentary. But it'd be fun to think about, you know, what Sondheim's career would have been like if he had become a designer of video games.

Barry Joseph: And that, in part, is what my book is exploring. I write about the people in his world who he connected with, who did choose to do that as a profession. And he wanted to have conversations with them, read their books, be in their communities that were solving crossword puzzles together, playing board games together in New York City. He sometimes didn't even introduce himself as I'm a musical composer. He would say, "Hi, my name is Stephen. I'm a game designer." And he would put on that a time. for a while.

Richard Schock: Wonderful.

Let's now revisit our friend David Spira, who joined us for both the episode on Escape Rooms, episode two, and Jigsaw Puzzles, episode five. David invited me onto his own podcast Room Escape Artists for the start of their 10th season alongside his co-host Pei-gee Law.

Barry Joseph: This clip is from the bonus episode available only to their Patreon supporters, but available now to all of you through their gracious permission. We took a deep dive into the origin of my over two decade interest in thinking hard about play, which set me up for writing this very book. But that's not my only reason for including it in this Give Us More episode. Well, there's a clue in here that might lead you to solve one of the Easter eggs in my book. With that bit of tantalizing teas, let's jump in.

David Spira: Welcome to the Reality Escape Pod Bonus Show. The bonus show. Today, Peih-Gee and I are joined by our episode guest, Barry Joseph.

Barry Joseph: Woo-hoo.

David Spira: And we're just gonna be hanging out a little bit.

Peih-Gee Law: Barry, you're so good at this. You should start a podcast.

David Spira: Truly.

Barry Joseph: I'm just punchy

Peih-Gee Law: I see here, Barry, that you came to escape rooms via ARGs and geocaching. Do you wanna talk about any of those?

Barry Joseph: Oh yeah, sure. I imagine your listeners are familiar with something called The Beast, which was the first augmented reality game.

David Spira: We've had Elan Lee on twice. He's one of the creators of it. This is a seminal ARG that really changed the world of immersive gaming. It kind of set the world of new media on fire at the time. There's a certain type of nerd from a certain type of era that this would've changed their life.

Barry Joseph: And you're talking with one of them right now.

David Spira: Have no doubt that Barry, you were one of them.

Barry Joseph: And if you weren't there at the time and don't know the history, the key thing is David just described the name of one of the designers, but when the game was introduced, it was done anonymously. We had no idea who was behind it. All we knew was that it was somehow connected with an upcoming movie called AI that was a movie made by Steven Spielberg, and somehow this was connected to that world. So it seemed likely it was somehow connected with the production. We didn't know it was from people at, I believe, at Microsoft who were exploring what this could mean, and I was one of those people who learned about it, not directly as the first people did, who saw the movie poster, saw the name, I think it was Jeanine Salla who was, I think the robot psychologist credited on the poster, and that's an odd role for someone to play. And if you Googled her at the time, it then took you to a website and that was in then portal into an alternative universe that lived initially in the web of interlocking websites from the timeframe of the movie, but then spilled over into the world around us. So that you could call a phone number and talk to someone in that world. I, at one point, was able to go to a bar in New York City, while other people were going to other locations in their cities around the country, and interact with the story as it moved forward in real time.

One day in my life was one day in the story's timeframe, and we had no idea who was behind it. I ended up on CNN. Just as one of many random players because I wrote a few things about it and maybe blogged about it and they couldn't talk to the people behind the game 'cause they were invisible. So there I was on CNN talking about what it was like to play this game and be part of this online community, on this website called Cloudmakers, where people were coming together to collectively solve the puzzles. It was a remarkable experience.

David Spira: This is really interesting 'cause we've had a few different guests on who were making some of these ARGs in the past, but we've never had anyone on who played them. To the best of my knowledge, at least. I'm curious, were there any moments from experiencing The Beast that like really stand out for you, looking back on them now?

Barry Joseph: Absolutely. And before I do, I'm gonna answer in a meta way. You are asking me to talk about what it was like to play a game and there's a new book that just came out that's about how valuable it is for all of us to learn how to build that language. It's called The Well Read Game. It is intentionally pulling from Bernie De Koven, from people inspired by him, and it's talking about how important it is for us to be able to articulate not just the strategies we did to solve an escape room, not just the strategies we did for how we sped run through a video game, but what we experienced in playing that game and how we applied what we learned from it into our lives. So what you're asking me to do now is to do that: describe what it was like to experience that game. The first thing I experienced for the first time in my life was what it meant to solve problems with other people, who I had that loose connection online. I don't really know them, but I know a screen name.

And seeing the power of a group to tackle something and how fast we could move. Crowdsourcing. That was a new phrase at the time. That was amazing. The second thing I experienced was how beautiful it was to have a designed experience where I could have ludological content blur into my real life. When I play a board game, I think about the concept that I've learned called the Magic Circle, where I'm now entering a space where I'm gonna do something different. I'm gonna take on a role. We're gonna interact with each other in ways we are given permission to do in special, unique ways. But then when the game is over, I step out of that magic circle. With The Beast the magic circle blurred, and I couldn't always tell when I was in it and not in it. So, for example, during the game, there was a moment where a character in the story was being held captive at the Statue of Liberty. And I'm in New York City, right? Where the Statue of Liberty is. And we were encouraged in the game to call the security guard to try and get them to release them.

And I'm reading online as people are making phone calls and reporting what that experience was. I was at work, I was in a meeting at the time, I could not call. I found out afterwards once the curtain was revealed and we knew who created the game and I'd contacted them, that they knew me. Why? ' Cause I was a great player? No. They saw me on CNN and they had done research and they were prepared with a script of what to say if I had spoken to them. That to me is one of my great regrets in my life that I didn't get to experience that collapsing of reality of when I called a phone number while I was at work talking to a security guard in an alternate universe, and he was going to, I was told, tell me, oh, you went to Northwestern class of 1991, and suddenly being like, wait, what's going on here? How do they know who I am? How does this character recognize me? How do they see me? And being seen by the game designers, just through the design of the play as part of this collective was a remarkable experience I've been trying to capture I think ever since.

Peih-Gee Law: Oh my God. That's like the movie, The Game. Like I think I might start developing a psychosis after that. 'cause already when I come out of escape rooms and you see like a pattern on a building and you're like, is that a puzzle? Like you start seeing puzzles everywhere. Yeah, I totally, I feel you. I feel like I wouldn't be able to stop living in that world.

Barry Joseph: It becomes a whole new way of engaging with the world around you. With, like you said, the pattern matching that we're so good at as humans, applying it in whole new places, in the ways you can connect with the people who you're with. I mean, in many ways, what's an escape room? It's a unique way to connect with people in your life.

David Spira: Absolutely. Yeah, I'm just thinking a lot about some of those really big emotional responses to some of these games when you first discover them. The first time we were ever featured in any kind of news article, it was in Newsweek. It was this piece that was written in 2015. And the closing lines of the article were about my friend Jason Casio, who was one of our regular teammates back in the day. Still a very good friend, and the article closes: " As they stand on the sidewalk saying goodbye. Casio looks at the restaurant awning studying the street address. Then he says. "When you play these games, you see numbers and patterns everywhere. You start thinking everything is a clue." And I remember that experience and I think New York was an especially strong place for that sensation because you wouldn't leave the games and get into a car. You would leave the games and you would walk around an old city filled with things new and old, and numbers and patterns and things that work and things that are broken there. Everywhere you look though, there's something to look at and it's all interesting. And so stepping out of an escape room in the early days for me and onto the streets of New York, you felt high, as you took in your environment, or at least I did.

Barry Joseph: And the dark side, of course, of all of this. Which has been well described by one of the founders of the Cloudmakers, that web community I talked about with the original ARG, is that this can lead many people into only feeling fed by conspiracy theories.

David Spira: Mm-hmm.

Barry Joseph: And trying to map them back onto the world, which has driven a lot of the MAGA movement.

David Spira: Yeah. I have talked about this in various forms where like: these experiences have definitely given me some amount of empathy for the conspiracy theorist. I get it. I get, at least I think I get some of it. It's really nice when you play these games that are architected for you. There's someone who's putting thought into it. It's not chaos because someone made it with so much intentionality. It's comforting to think that. Yeah. Even if they're nefarious, that somebody actually has control of all of the chaos out here.

Barry Joseph: You feel seen.

David Spira: Mm-hmm.

Barry Joseph: In an escape room. We agree to let someone have complete control over hearing everything we say and do, but it's consensual and that relationship is an interesting relationship to think about.

David Spira: Mm-hmm.

Barry Joseph: And that relationship is the same one that we had in The Beast where a group of anonymous people with motives that we couldn't see, were watching everything we were doing and responding to it. The community was solving puzzles faster than they expected, and we watched them change what they were doing and those kind of relationships of being seen I think as part of the conspiracy theory, attraction of people who don't feel seen, being seen, even if they don't know who's behind the conspiracies or those advocating for those conspiracies.

David Spira: I see that. I am also curious. What was the process like of unmasking for the creators from your perspective as a player?

Barry Joseph: So a few things happened. One, it was revealed who it was, and you might be better positioned than me to say who they were and what they were doing at Microsoft. But what they also did is they honored us. They honored us, was the thing that they were connected with. Not the ARG itself, which ended, but with the movie. And there was a showing of the movie, free, for all of us in the New York area to go to. And at that screening we were given a custom version of the poster. I'm getting a little choked up even just describing it. The poster, if you don't recall it, is the letters AI that are also designed to look like the characters.

David Spira: Mm-hmm.

Barry Joseph: They changed the poster and they changed it so it was composed of all of our screen names.

David Spira: Ooh. Do you still have this poster?

Barry Joseph: I kept one thing from my experience with the Beast, and it was a bandana that I received at the bar where we met in person for the first time. And it was valuable to me 'cause it was during the play of the game.

David Spira: Mm.

Barry Joseph: The game had went from my telephone and my emails and the websites to being in the real world around me. And this was a physical manifestation of this virtual world. And so I love that about it. I regret, however, not saving that poster, but it's okay that I didn't, 'cause I can remember it in my mind and I can remember that what they were saying was this game that they created was us.

It was made out of us solving the puzzles, out of the decisions that we made, and how it pushed them as game designers to go to places they never imagined and how we did it together.

Peih-Gee Law: I think that is a great place to leave this episode, the Power of Games, bringing community and people together. Barry, thank you so much for joining us.

That poster mentioned about AI, you can see that in the show notes for this episode. Also, you may have caught the callback to Bernie De Koven, his book, the Well Played Game, and a new book that takes inspiration from it: The Well-Read Game- On Playing Thoughtfully by Tracy Fullerton and Matthew Farber. More on that in the show notes. And here for a little bit of fun. Here's a clip from that CNN bit from almost 25 years ago.

James Satori: Hi everybody, and welcome to CNN.com I'm James Satori. We begin this week with an online mystery: Who killed Evan Chan? Did he really have an affair with a robot? And what's all this got to do with Steven Spielberg's upcoming film AI? Well, it's either a case of conspiracy minded webheads spinning their own cyber fantasies, or a calculated public relations ploy to drum up interest in a Hollywood blockbuster. Or both. Over the last month and a half, the unfolding web of intrigue has attracted thousands of fans who've discovered this backstory game.

Barry Joseph: As we move through the game, little pieces keep unfolding and we might, it might come through an email. A piece of it might come through a telephone call.

James Satori: Players are reveling in the intrigue.

Barry Joseph: This relationship that's developed between us and the puppet masters, knowing that they're watching us, that maybe they're part of the game. Maybe I'm one of them. We have no way of knowing.

Okay. I think we now know and knew then as well. I was not one of them. Let's now return to my final segment with Richard, after, which we'll have an epilogue of sorts. Listen in now, as I awkwardly correct a perceived error in Richard's book when for the only time he uses a games lens to analyze what we can learn from Sondheim, and before Richard concludes with advice for me in what at the time was mere weeks before my book was launched, which is advice I think holds for any author. And I hope his words help you as much as they did for me. This next one is a little bit awkward for me because it's the only thing that we both address in our books. It's the one time in the book where you're writing from my lens. You're writing in the book about Sondheim and his puzzles.

Richard Schock: Is this the Japanese puzzle box?

Barry Joseph: Yep. but I'm not sure I agree with how it was represented. So I want to explore this with you. So on page roman numeral 15 is the, "in his Manhattan townhouse."

Richard Schock: Uh huh. Okay.

"Unlike a jigsaw puzzle, where the goal is to assemble interlocking pieces to form a complete picture, the point of a puzzle box is to figure out how to dismantle it. This, to me, seems the perfect metaphor for what Sondheim's works accomplish. He doesn't put the pieces of life back together again. He takes them apart. What Sondheim offers us is not life with all its riddles happily solved, but life deconstructed and laid bare in all its confusion and disarray.

Barry Joseph: I love the ideas in there, but I need to dig a little bit deeper with you if we can. And I'll read you the one line that you then use as a callback at the end of the book on page 235, where you say, summarizing everything, "Life is less about solving the puzzle. Remember, Sondheim dismantled his Japanese puzzle boxes, then putting up with the puzzlement." And dismantled is italicized. Can you say what you mean about dismantling? And I don't mean in the abstract way, but specifically with the puzzles, so I can make sure I'm on the same page with you first before I ask you my question.

Richard Schock: Right. And, and, and here I'm happy to take guidance from you, 'cause maybe I have misunderstood something. But the reading and research I did about the Japanese puzzle boxes led me to believe that what you do is figure out how to take it apart, to actually dismantle it. You sort of decompose if you will, decompose the puzzle box. And I thought this is a really interesting metaphor for how Sondheim's works work. if you will, they don't, fix the problems of life. They don't solve the problems of life. They expose the truth of life. And that truth is often messy and uncomfortable and difficult to go through, and I just thought in a figurative, metaphorical way. So I was using the actual object of the Japanese puzzle box to make a metaphorical point that Sondheim's works don't solve the problems of life so much as they lay bare all the problems of life and then say, "well, how about that?" But have I misunderstood how Japanese puzzle boxes work?

Barry Joseph: I love your lesson, and let me see if I can help it still connect back to it.

Richard Schock: Okay.

Barry Joseph: When I read it, I thought maybe you were conflating the type of physical puzzles that someone might find in like a doctor's office where you take pieces apart or put them together in a puzzle. What these boxes are, these Japanese wooden boxes hide pieces that are not apparent in their ability to be moved. And if you can identify that, they shift in ingenious ways in order to, for example, open a drawer. So it's more about getting inside them than about taking them apart, but I think the metaphor can still work. Sondheim loves puzzles, but he loved different things about different puzzles. With these kind of Japanese puzzle boxes, he loved their design more than he enjoyed the act of solving it. He told Meryle Secrest, which you can hear in the interviews from Yale, that he just wasn't good at them. He liked being engaged with the process of solving them and learning their hidden designs. Not necessarily getting to the end, the opening or the dismantling, as you say. That state of traveling but not arriving, of solving but not having solved, I think that is very aligned with the beautiful point that you make in the conclusion of the book. But it's not because he dismantled the puzzle boxes, but rather they provided him with an opportunity to contemplate the mystery of hidden designs.

Richard Schock: Barry, thank you so much. I'm really grateful to you for explaining in your expert way, how those Japanese puzzle boxes work. And you've given me a lot to think about. And when the paperback version comes out, I'm going to make sure that I have revisited those sentences so that what I say is technically true to the design and operation of those puzzle boxes, while also keeping the metaphor, the, the image of Sondheim, laying life bare. But just as I say, I don't mind when readers disagree, I love and appreciate that you have paid me the compliment, if you will, of taking the work so seriously that you have corrected it. So thank you very much. I appreciate that. "By your pupils you'll be taught" as Hammerstein said. Not that you're my pupil, but you know what I mean?

Barry Joseph: Your book, it is teaching me every time I open the pages.

Richard Schock: That's kind.

Barry Joseph: And I appreciate your taking the feedback and considering how to adjust it because the last thing I'd want you to do is to remove that lesson from the book because it was so important for me when I read it.

Richard Schock: Thank you. I appreciate your advice.

Barry Joseph: So Richard, now that your book's released, can you share a few words about what it's like to have written a book about Sondheim and have a book about Sondheim go out in the world and associate it with you? And in conjunction with that, now that my book is about to be released, do you have any advice for me?

Richard Schock: It's one thing to write a book, that the author can control. The author has control over what's on the page. But after that, at least this is my experience, the author has to start surrendering control. We talked about the cover and the image and the title and other people are making decisions.

Although I love my publisher, Atria books in the US, Ebury Publishing in the UK, but they have to do what they have to do. And then the book comes out into the world and you have no control over what happens. You hope the book will be reviewed, but you don't know. You hope the book will get some publicity, but you don't know.

You hope that people will like it, but who can say? And it, on the one hand, is a terrifying experience, because you don't write a book overnight. This is sort of a multi-year process from start to finish, and then you have no idea what is going to happen. So I feel really blessed and I'm not using that word in a sort of a cliched way.

I feel really, it's been a great gift in my life. Not the writing of the book, the gift has been that the book has found the people for whom it was written. And Barry, I know we've joked a bit offline that I found out through you that the book was the cover of the New York Times book review on the Sunday, the weekend just before Christmas, which is of course every author's dream.

But who knows how and why that happens. I think it was something about the New York Times loves Sondheim. Gypsy had just opened. So, again, the stars sort of aligned, but you can't make those things happen. Not even a publicist in a publishing company can make that kind of coverage happen.

So, it's been gratifying that the book has been reviewed in some high profile places, the Washington Post, the London Times, the Irish Times, they've been favorable reviews. The book has gotten some publicity. That so many Sondheim fans on "Finishing the Chat" and on Twitter and Instagram, have helped to spread the Sondheim word has been wonderful.

I see on Facebook photographs of people I don't know holding the book saying- I got this book for Hanukkah for Christmas, and I've really enjoyed reading it. And they've taken the time to help spread the word, I don't want to say kindness of strangers because for me, readers aren't strangers as the people I have always had in mind when I wrote the book, but they've been so incredibly kind.

So, writing the book was a rewarding experience, but watching the fate of this book in the world in some ways has been an even more rewarding experience. And I'll go back to the word we were using before, "connect". Because I felt, I, Richard, the book and readers have connected and that is a powerful experience.

So it's been a wonderful journey for me. It's not quite over. It continues. The song goes on. But it's been wonderful. And you asked, you know, advice, as a book finds its way. And in some ways you're well ahead of the game, Barry, because you are already part of the community and engaging with that community.

So many, many people are now waiting with excitement for your book and will be primed to read it and celebrate it and spread the word and tell other people about it. But then on the other side, if I were to offer you any advice, it is to remember that the core of it all is the author writing something they're proud of and whatever happens next is not within our control.

It can be wonderful. It could be miserable. I don't think it will be in your case. But the core of it is the author writing with integrity, being proud of what they've written. And that's the gold. That's the true gold. If other kinds of quote unquote "success" happen, that is wonderful. And that's to be cherished and that's to be savored.

But the ultimate success is for an author to say, "I wrote the book I wanted to write". And I do believe that.

Barry Joseph: Thank you, Richard. Thank you so much for joining me today in conversation.

Well, where to go from there? I think only forward. It is now, today, on this date in November, six weeks since my book was published, and Richard's advice has been so valuable. The book is out and I'm learning to release it to the world and to enjoy watching others discover it and make it their own.

Each day is full of gifts, recommendations on GoodReads and unboxings on Facebook, reels on Instagram, private messages on social media and more. Here, for example, is first Ben Zimmer and Mignon Fogarty talking about my book on her podcast Grammar Girl, followed by Donald Feltham on his Broadway Radio Show.

Mignon Fogarty: So I guess to finish up, we'll get your book recommendations because we always do that. We love to hear the favorite books of our guests. So what are your three recommendations?

Ben Zimmer: I'd like to recommend books that are coming out this fall. The author is Barry Joseph and he wrote a book called Matching Minds with Sondheim: the Puzzles and Games of the Broadway Legend, and it's published by Bloomsbury. I was able to read, an advanced copy of it that Barry Joseph shared because I have this interest in Stephen Sondheim who, uh, you know, lovers of Broadway musicals will know his incredible aptitude with language and wordplay that enters into lyrics of songs and that sort of thing. But he was also an avid puzzler including his penchant for cryptic crossword puzzles, this British style of crossword that he helped introduce to American audiences when he was making these puzzles for New York Magazine for a couple of years. And in his private life, he was surrounded by games and puzzles at all times. After he passed away, his estate auctioned off his various collection and of all sorts of sort of puzzle and game material, and Barry Joseph sort of documents, everything that we can learn from his mind. This sort of, you know, the puzzling mind of Steven Sondheim from all of that. And, uh, it's just, it's just a lot of fun for fans of Steven Sondheim or fans of puzzles or both, you know?

Mignon Fogarty: Yeah. Two different worlds. That's fascinating.

Ben Zimmer: Yeah.

Donald Feltham: Welcome to the Broadway Radio show. I am Donald Feltham. I have a wonderful book to talk about on this episode and the authors here to chat about it. It is a book focusing on Stephen Sondheim. And before you say to yourself, do we really need another book on Stephen Sondheim? Let me tell you that this book is intriguing, fascinating, entertaining, and a must have if you want a deeper understanding of who Stephen Sondheim was, and if you thought you knew all about Stephen Sondheim, you are sorely mistaken, as you will find out when you read this book, and you will not look at or listen to a Stephen Sondheim musical the same way again.

Barry Joseph: Finally, what people have told me directly has floored me. At a talk in Cherry Hill, New Jersey during the Q&A, someone shared:

Robin Sue: So, being a Sondheim fan, this explains a lot.

Barry Joseph: And finally with the last word, reader, Adam Brooks posted the following on GoodReads. I think this book may be the most personally affirming thing I have ever read. I've spent plenty of time reflecting on the spiritual nexus of puzzles, games and theater writing, and this book was everything I could ever hope for and so much more.

It showed the brain and heart of one of my heroes was way more like mine than I ever could have imagined. The breadth and depth of scope are so unbelievably satisfying. It boggles my mind that such a significant piece of Sondheim's being when so unexplored until now. Barry has done an incredible service for multiple communities, and as someone living at the nexus of many of them, I've never felt so connected. If you love Sondheim, puzzles games, or like me, all of the above, you'll never find a more fulfilling and validating piece of writing. Wow! As Richard said, the book and readers connecting is a powerful experience. And that's what I hear in both of these quotes, moments of clarity and moments of connection, the two themes I aim to express in Matching Minds. Thank you all for affording me this opportunity through these podcasts to give you more to hear. I would also like to thank everyone who contributed behind the scenes to this episode: Jay Bushman for sending me the wonderful CNN piece from 2001 on the Beast A.R.G., the musical stingers, composed by Mateo Chavez Lewis, our new line producer Dennis Caouki, and the theme song to our podcast with lyrics and music by Colm Molloy and sung by the one and only Ann Morrison. Until next time, remember, someone is on your side, especially when matching minds with Sondheim.

James McCusker: Sheila is a gossip columnist. Sheila is dead.

Barry Joseph: That's it. That's it.